It’s As Lethal To Us As It Is To Our Enemies

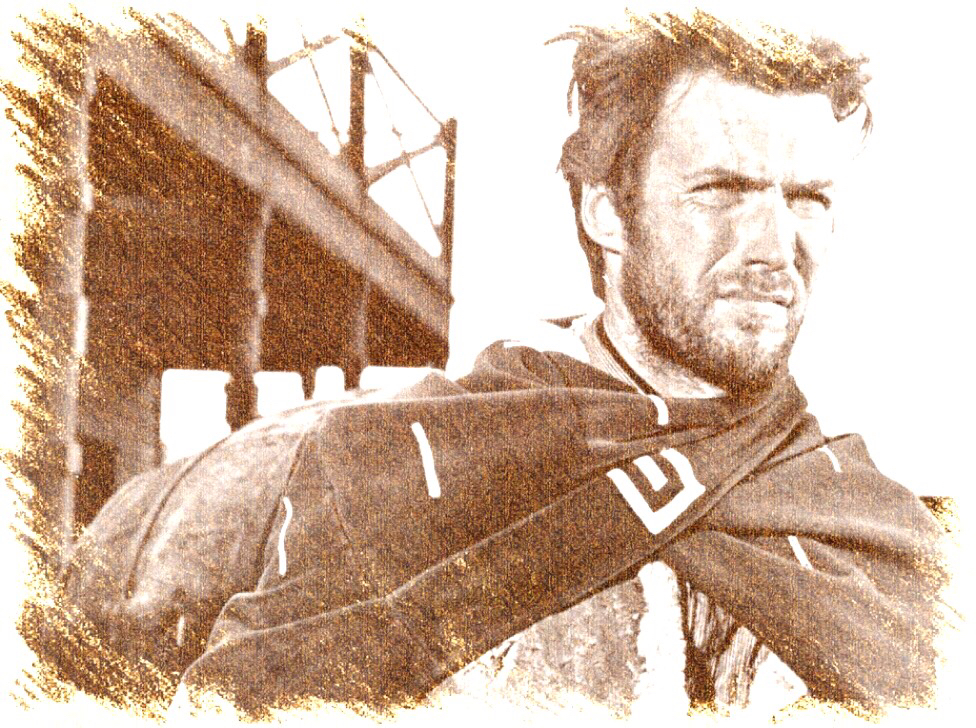

Let me say up front that I’m a Clint Eastwood fan. But to the extent he’s a publicist and apologist for American wars of aggression, count me out.

When I was a kid, Rawhide was a staple on our TV-but what’s really stuck with me is the theme song: “Rollin’ rollin’ rollin’”

Then there was Eastwood as the ultra-tough, cigarillo chomping “Man With No Name” in the Spaghetti Westerns. My junior high school buddies and I use to love climbing aboard an old Denver Tramway bus, dropping a dime in the fare box, and riding downtown to watch Clint gun down Eli Wallach at the elegant Paramount Theater.

I took a break from Eastwood during his Dirty Harry period. Although I can’t remember for sure, I imagine that I thought that I was too sophisticated by then for films that resolved all problems with a magnum .45 revolver. The boycott continued with the orangutan (?!!) in the Every Which Way franchise; too silly to even give it a thought. It was years before I seriously paid attention after that.

The movie that got me back on the band wagon was Gran Torino. And, of all places, it happened at the YMCA camp at Estes Park during a retreat for men at my church. Led by a gifted pastor, Rich Pilon, we watched the film. And then discussed its significance, including the obviously Christian symbolism as Eastwood, arms outstretched, dies in a hail of bullets to save a family from the savage predations of a criminal Hmong gang.

Sure, the film was imprinted with Eastwood’s trademark violence. Or, rather, threat of violence-he doesn’t shoot anyone. But it was far more than that. It was thoughtful. And thought provoking. At multiple levels.

And best of all for me? It touched on some of the taboos, like the high rates of black crime, which the rest of Hollywood so often misrepresents as the fault of a racist judicial system. Imagine seeing this Gran Torino scene featuring black thugs in your typical Hollywood film. You can’t-because there aren’t any. (Interestingly, the cowardly, white “wanna be” thug in the scene is Eastwood’s son, Scott.)

Shooting Ourselves In The Foot. Or Worse.

My most recent encounter with an Eastwood film was in our basement where, while working out on the elliptical, I happened to catch some snatches of American Sniper between flipping back and forth to avoid commercials. The title alone was a dead give away: the war in Iraq.

I came in very near the end of the picture. Scenes follow in rapid succession. The lead character, Chris Kyle, is visiting maimed soldiers in a hospital. He’s working the spotting scope for legless soldiers in wheel chairs at the rifle range. He’s horsing around with a big pistol in the kitchen. He’s bidding his wife and two little sons goodbye at the front door. A foreboding shadow falls across the wife’s face.

At that point, I turned it off. I couldn’t bear to watch what I thought would be the inevitable conclusion: suicide. According to a recent VA study, 20 veterans a day die from suicide. More active service soldiers are succumbing to suicide than are being killed in combat.

And, sure enough, when I turned it back on a few minutes later, it’s Taps, the grieving widow, and the honor escort to the cemetery. A suicide for sure, I thought.

Nonetheless, I put the film at the top of my Netflix list and watched it without commercial interruptions-but in segments that lasted only as long as I could endure the elliptical.

There’s nothing understated or subtle about the harrowing combat scenes of this film; the bodies pile up like cordwood. Mostly, of course, they’re anonymous Iraqi insurgents-for whom most of the audience feels no sympathy.

Our sympathies are reserved for the relatively few American casualties. And, above all, for Kyle’s wife, Taya, as she endures four interminable deployments while trying to raise the kids of a father who is more often absent than not. For obvious reasons, the marriage is on the rocks for a good part of the film. And, sure enough, studies have shown that lengthy deployments significantly increase the risk of divorce among military couples.

This is a great film. But almost certainly not for the reasons that made it the highest grossing US film of 2014. And the highest grossing war film of all time. Or Eastwood’s highest grossing film to date. No, the money is mostly about the shoot ’em up, the gripping suspense and the heart tugging human interest.

The Ripple Effects of Failure

No, this is a great film, because hidden in plain sight, it tells a story that cries out to be told: the calamity the war in Iraq has been for all involved. America. Iraq. The US military. And, perhaps most importantly, for the last vestiges of the notion that our country remains a limited republic. Rather than a hideously overextended empire that is infected with all the vices that, if God is just, will inevitably lead to its fall.

The human costs to this country are almost unfathomable. And are prominent in the film. Nearly five thousand dead. Tens of thousands of amputees, countless traumatic brain injuries and cases of mental illness, including suicides. The enormous psychic toll extracted from the spouses, children and families of these physically and mentally maimed soldiers is a harrowing subtext of Sniper.

It’s almost obscene to set these human costs against the ruinous financial expense of our military adventure in Iraq. But to fail to do so would be to ignore the elephant in the room of the movie. Credible estimates from the CBO and others run as high as $3 trillion. Most of which, of course, is borrowed.

While the film doesn’t touch directly on the financial burden of the war, it can be inferred from all the high tech, high cost weapons that constitute the American way of war. And which figure so prominently in the movie. But while gold plated weaponry hasn’t won the war, it sure has fattened the wallets of defense contractors and their lobbyists. And allowed Congressmen to boast about “bringing home the bacon” when their district lands one of these lard laden plums.

Despite the undoubted courage of the American soldier, the film also makes clear it that we are no closer to “winning” now than we were when we first invaded Iraq fourteen long years ago. (Even the ham-handed Soviets had the good sense to get out of Afghanistan after 10 bloody, futile years.)

And, this, despite the fact that the US is fighting an enemy that, relatively speaking, is armed with cheap, nearly stone age weapons: AK-47s, hand held rocket-propelled grenades, and improvised explosive devices. But, more important than any weapon, an enemy also recklessly determined to defend his family, home, religion and country.

But if the human and fiscal cost of this interminable war has been high for this county, it pales by comparison with the price that Iraqis have paid. Again, this is not a topic Sniper dwells on; but, once more, it’s hiding in plain sight. Massive military and civilian casualties are the inevitable byproduct of the extraordinary violence that American weaponry rains down in a conflict largely fought in a densely populated urban setting. And there are more than enough gory scenes of “collateral damage” in the film to drive home the point.

While estimates of Iraqi casualties vary wildly in the fog of war, they fall somewhere between 100,000 and 1.2 million. It’s beyond doubt, moreover, that many of these casualties are non-combatants: women, children and the elderly. Add to this the untold misery of the millions of Iraqi refugees and displaced persons that have been generated by the war, and to describe the conflict as a “calamity” is an understatement.

The Federalist Papers is the Rosetta Stone for understanding the US Constitution. The catalogue of evils the Founding Fathers ascribed to standing, professional armies is well documented in the book: my edition has no less than 10 entries under the “standing armies, fear of” heading. Among them? The crippling expense. The threat to liberty arising from the danger that citizens will come to look upon the military not as their protector, but as their master.

But what is most tragically ironic is that the book convincingly makes the case that this country doesn’t even need the gargantuan military establishment on which we now spend more than the next 8 nations combined.

Why? Because last time I looked, the map shows that this country is still surrounded by massive oceans. In the Federalist No. 8, Alexander Hamilton argues that our situation is comparable to Great Britain’s which, due to the much narrower seas that border it, hasn’t been successfully invaded since the 11th century. And, therefore, requires no more than a robust navy and and a small army.

Of course, I know that in the jet age we need an air force to protect us from intercontinental bombers. And, even more importantly, an airtight missile defense given the world’s nut jobs, including the one in North Korea.

But why does a bloated, exorbitantly expensive military like the one with which we are currently burdened make any sense unless we’re enamored of playing the bumbling world cop? Or we just like picking fights? Or feel compelled to provide material for horror films like American Sniper.

So, hey, how’s this military industrial complex thing working out for us? Not so well? I agree. The catastrophes that have befallen our misadventures in Vietnam to Afghanistan and now Iraq amply prove the point. The Soviets learned their lesson. Why can’t we? Or, if we’re too proud to learn from the Russians, can’t we at least heed the advice of our Founding Fathers?

Let’s celebrate being on the same page here. You nailed this one. I saw Gran Torino twice.

I like being on the same page!

Suggest the book “Kill Chain”.

PAUL. Thanks for the visit

Paul. Put your book on your front porch. Interesting and thanks!