Past. Present. And FUTURE.

Hit the rewind button. Again. Back to the Black Hills and Mount Rushmore for a couple of nights at the beautiful State Game Lodge. I stayed there as a kid with my mom and brother on two trips we made to visit her relatives in far southeast North Dakota.

The Lodge seemed huge then; small now. One night, my brother and I sat out on the big front porch, watching a fierce storm, the lightning bolts turning the surrounding hills white before they were plunged into an even greater blackness. Thunder claps coming from just over our heads and then tumbling down the valleys, the rain sluicing in curtains off the roof in front of where we, mesmerized, sat. The show was over too quickly.

Those were lean times for our family; my dad had gone from driving big Cadillacs with those outrageous tail fins to a little VW bug with faded, orange paint. But it did the trick, laboring up those long grades in Wyoming, getting us to mom’s relatives’ farms in southeast North Dakota. Those farmers-those relations-are mostly gone now.

Angry hornets.

Custer State Park is something like a beekeeper’s veil: it keeps at bay the annoying swarms of tourist traps that would otherwise overwhelm Mount Rushmore, the Crazy Horse Memorial, and Badlands National Park.

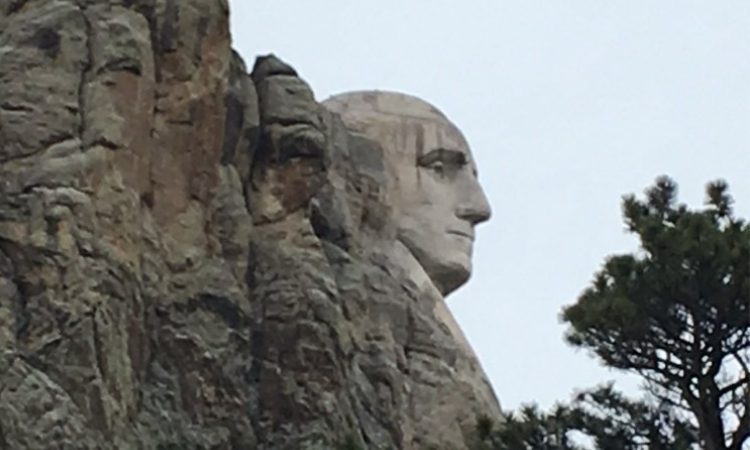

Mount Rushmore in a driving rain, sleet mix is less than ideal. But look on the bright side-I pretty much had the place to myself. And the weather did nothing to deter those stoic, gray figures, their faces wreathed in mist, gazing out towards the horizon.

Persistence and determination are alone omnipotent.

A few miles down the road, it was the same story at the Crazy Horse Memorial, where the massive sculpture pranced in and out of the clouds.

In 1939, Lakota Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear wrote a letter to the well known Polish-American sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, asking him to create a monument so that “the white man would know that the red man has great heroes too.” Although Ziolkowski answered in the affirmative, the start of the work was interrupted by the sculptor’s WWII Army service; he was wounded at the Omaha Beach landings.

The first blast on the sculpture didn’t come until June 3, 1948. The work hasn’t stopped since. Not by Ziolkowski’s death in 1982. Nor his wife Ruth’s death in 2014. It’s now carried on by their 10 children and even grandchildren.

When I first visited Crazy Horse with my mom and brother back in the early ’60’s, you had to have an active imagination to have any idea what was taking shape on that distant pile of rocks. No longer. Crazy Horse’s face is finished, even though it will be years, if not decades, before the entire sculpture is. (This glacial pace of progress has been the object of some criticism and charges of family nepotism.)

Why has it gone so slowly? It’s all been done with admission fees and private donations. When federal aid was offered, Ziolkowski and the tribes he worked with refused. When I asked one of the museum attendants, “Why?” he answered, “The federal government took our land. We’re not going to take money from them.”

Past. Present. And future.

When Monique Ziolkowshi, Korczak’s daughter and now CEO of the undertaking, is asked when the sculpture will be finished, she replies, “I’ll be dead before it’s done.”

Is this monument, which this woman will never see completed, a strange project to devote one’s life to? Maybe.

But isn’t it a sort of picture of how life should be lived? Hopefully, our ancestors have bequeathed something to us we consider worth preserving. A tradition, or, as Burke had it, a “prescription,” that we carry into the present. And that we, in turn, live, move and have our being in such a way that makes “the Permanent Things,” as T.S. Eliot described them, beguiling to our descendants.

Nice photos–thanks for sharing!

Thanks. Coming from someone who’s clicked the shutter as many times as you, that’s saying something.

I’m not quite to a million yet, but I am getting there 🙂

Thanks a million-for dropping by.