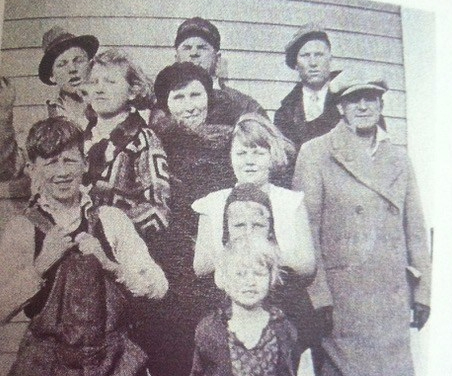

Joyce, with the windblown buster brown cut, surrounded by her family on the North Dakota prairie. Before the Depression was over, they had all been blown off their farm.

My 93 year old Aunt Joyce died recently. She was the last but one of my mom’s six siblings. Joyce’s was a life well lived. The funeral and celebration were in Boise, her home town. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

My sister, Linda, and her husband, Jim, came in on the same plane from Denver with me. We met up at the luggage carousel. Jim and Linda are well acquainted with these devices; since they retired, and even before, they have seen more of them in more different parts of the world than I can even begin to guess at. But aside from the two of them, I didn’t see anyone else in the terminal who would be at the funeral.

“I hope we get a good turnout,” I said, watching the bags begin dropping off the conveyor belt. “It would be a shame if we can’t give Joyce a good send off.”

“I know there will be more, but I don’t know how many,” answered Linda. “You know how funerals are; not much notice. We’ll just have to wait and see.”

With that, her bags came around and they took off to get their rental car. My bag came a few minutes later and I headed out of the terminal; I was going to be riding with my cousin, Mike Lee, another of Joyce’s nephews.

When I got to the sidewalk, Mike and his big F-100 pickup and camper were to my right. As I headed his way, we both raised our arms in greeting. Mike is a character. And a guy with an interesting history. After graduating from Nampa Nazarene University just west of Boise, Mike went “North to Alaska” where he spent most of his career as a park ranger. But also on his resume are bush pilot, moose hunter, dog sledder, snowmobiler, cross country skier, and logistical support for fighting forest fires. Now retired, he spends summers in Fairbanks. He winters in the Northwest where he lives a semi-nomadic life from his camper with family and friends.

“Mike,” I said as we shook hands, “how are you? Thanks for picking me up. I’m looking forward to catching up. Are we going to head right over to Monica’s?”

“Yep,” replied Mike, “that’s where everyone is gathering.”

“Remember,” I said as we left the airport, “I’m buying the gas.”

We left the airport, got on I-84 and began rolling west toward Eagle. When I was a kid and we drove from Denver to Boise for fondly remembered summer vacations to visit family, Eagle was a small farming hamlet. Now, it’s being swallowed up by nearby Boise, where big box stores incongruously bump up against rapidly disappearing fields of alfalfa and corn.

Monica Davis, Joyce’s very successful mortgage broker granddaughter, lives in Eagle and was playing host for the the celebration. Monica has a spacious home with a kidney shaped swimming pool in the backyard. She’s generous with her house; over the years, many similar family gatherings have taken place around that elegant little pool.

With the limited visibility afforded by his rear view mirrors, Mike awkwardly maneuvered his big rig into a space at the end of Monica’s cul-de-sac. And, as we have done several times before, we let ourselves into her home through the garage. I couldn’t help ogling a curvaceous Alpha Romeo that was partially visible behind a mound of stuff and a car cover. “Just like Monica,” I thought, “to drop a bundle on a car like that and then let it gather dust in the garage.” She also likes Las Vegas, where, I’ve heard, she qualifies as a “whale.”

We stepped into the kitchen down a short hall from the garage. The food, as usual, was spread over wide kitchen counters just inside the sliding glass patio doors. It was not so much a meal as grazing; just the way the Lee family likes it. At least judging by the amount of food that appeared to be in the offing, my concerns about an inadequate turnout for the event were badly misplaced.

On a nearby end table, there was an urn with Joyce’s ashes. Again, just the way she would have liked it; in the middle of the action and near the food.

My other sister, Catherine, also from Denver, was already there. When Mike said he had heard that she “likes the finer things,” he pretty much hit the nail on the head with her. Peter, Catherine’s son, was also there. An REI executive who looks the part, Peter had come in from Seattle for the weekend. Following his mom’s lead, he had developed a warm relationship with Joyce over the years. But, taking his cue from so many smart and perfectly eligible young men these days, he can’t seem to get the wife and kid thing figured out.

I recognized many of the other faces; the names were going to be more of a challenge. It had been a long time since I had seen many of them; a few were strangers.

Mike’s sister, Joy, stepped forward with a broad grin on her freckled face. “Spencer! How are you? It looks like we’re going to have a good turnout for Auntie!”

“Boy,” I replied, “you got that right. It’s great to see you. How’s . . . Craig?” I hesitated before I could summon up her husband’s name; I didn’t see him there. Joy and her husband, live on a farm near Pendleton, Oregon. But that doesn’t, of course, mean they make a living farming. She’s supplemented their income driving school busses, taught, and worked somewhere in the welfare system. He commutes back and forth to Portland every week, where he is a supervisor at a factory, living out of a camper. Aside from Monica, Joy and Mike were the ones Joyce relied on most during her last years in the nursing home.

Joy and Craig, if possible, are even more conservative than I. Which places them somewhere to the right of Attila the Hun. Unfortunately, that hasn’t immunized her family from tragedy. A drug addled daughter who lives in Alaska recently witnessed her boyfriend get murdered in a drug deal gone bad; Joy went to Alaska to provide moral support during the trial. The daughter, to my knowledge, hasn’t changed her ways.

There’s a strongly Nazarene musical thread that runs through the Lees-although it bypassed me entirely. Joyce loved to hear her nieces and nephews perform. Byron, Mike’s half brother, sang for years with the Seattle opera. Mike carries a rich base harmony line to the old time Nazarene hymns that he’s always itching to sing. Joy sings and plays the electronic organ, which she had brought along for the event. Merilee, Mike and Joy’s sister, has a sweet voice and is a pastor’s wife. The quartet led us in song as the sun began to find us under the porch.

I could go on; the weird uncles at what, in effect, was a family reunion provide endless fodder. There was the fundamentalist preacher with the wide, crucifix tie that faithfully preached at Joyce’s nursing home. Joyce, just as faithfully, had planted herself in the front row of his nursing home flock on Sunday mornings. And, as a result, he was asked by Monica to officiate. But, within a few minutes of his launching into his fire and brimstone sermon, it was obvious that Monica had played hooky at every one; she had no idea what was in store for us. To her obvious discomfort, the sermon went on way too long for her liking. But who knows? It may have hit someone right where they lived.

A weekend, in my mind, is just about right for an event of this sort. Long enough to reconnect with most of the folks I yearned to. But not so long that our inevitable annoying tics overshadowed the era of good feelings.

The next day, Mike gave me a lift back to the airport. Jack in the Boxes, luxuriant potato fields, shopping malls, and rows of corn snapped by on either side of us as we drove east on I-84 through the Treasure Valley.

Over the growl of the motor and the hum of the tires, I said, “Mike, that was a great weekend. I’m really glad I was able to make it.”

He gave no sign of hearing me; he may not be stone deaf, but it’s a tolerably good imitation. I turned up the volume another notch and tried again.

“You’re right,” he said this time. “Joyce would have liked it.”

“I only have one regret,” I added. “None of my kids were here. Next time, I’m going to do a better job of encouraging them to come.”

And I will.

A very nice remembrance of that day, Spencer. But just want you to know I was part of all the special singing group and in fact, l was the one who spoke to Monica and suggested the music we sang. Why? Because it was the same six hymns Joyce and I sang every time I visited her in the final 10 years of her life, whether at mother’s place, her place or her final place. I brought her a great CD of the Forester Sisters 🎶 ing all the great old hymns and both she and I knew them all. Not that we were the only family members who knew them or sang them, but it was something Joyce and I did when we were together. She couldn’t read a note of music, but she knew how to sing!

Sent from my iPhoneThank you for returning my call.

>

Thanks for the response. The Lee musical gene certainly didn’t pass you by.

Sent from my iPad

>