Our son, Byron, is a smart guy. But, growing up, he was not big on school. He much preferred to spend his time reading books. I don’t know how many times he read the Civil War epic, Rifles for Watie. And he almost certainly doesn’t either.

Our son, Byron, is a smart guy. But, growing up, he was not big on school. He much preferred to spend his time reading books. I don’t know how many times he read the Civil War epic, Rifles for Watie. And he almost certainly doesn’t either.

It drove us, and particularly his mother, nuts to be aware of his wasted potential. We tried a private, alternative high school for a while. It was a goofy waste of money. I suggested that we send him to a military academy in Kansas-my wife vetoed that idea.

When he got older and could learn to drive, we thought that preventing him from getting his license might motivate him. Wrong. He sat in his room and read. And brought home, at best, uneven report cards. Some A’s and B’s, a sprinkling of D’s and F’s. We gave up on the license thing when it dawned on my wife that if he didn’t learn to drive before he went to college-if any of them would accept him-he would be learning to drive from other college kids. Probably not the best teachers. We surrendered, he won. But he never seemed to really be all that interested in driving anyway.

He ended up going to Miami of Ohio-talk about a university with a geographic identity crisis. Why a school of its caliber would accept him I don’t know. Well, actually, I do: they wanted our money.

As he did at Cherry Creek High School, he played in the marching band. We went back for parents’ weekend and were there for the homecoming football game. Those were the glory days of RedHawk football-Ben Roethlisberger was the quarterback. So we got to see our son march at half-time. And Big Ben win the game.

But it was all pretty much down hill from there. Toward the end of the spring semester, we got a letter from Byron’s room mate informing us that he almost never went to class and did very little besides stay in the dorm room playing computer games. The room mate also reported that he had to work to pay his way through school. The kid was justifiably angry that Byron was not even warming a chair in class while he was working his fanny off.

When I picked up Byron at DIA that spring I showed him the letter. “What do you have to say about this? Is this what’s going on?” My voice quavered with anger as we drove along Pena Boulevard. He didn’t deny the contents of the letter. I told him, “We’re done with this. If you want to keep going to school, you’re picking up the tab yourself.”

A few minutes of stoney silence passed before he said, “I went to see the Navy recruiter recently. I think I’m going to join the Navy.”

“Right,” I replied, still upset, “I’ll believe that when I see it.”

“I actually took the the military IQ test, the ASVAB, and got the highest available score. They’re recruiting me into the Navy’s nuclear program.”

“Well,” I replied, “that sounds like it could be a good plan. But you’re going to have to prove to us that you’re serious.”

But, skeptic though I was, a few weeks later a couple of impressive, ram rod straight Naval recruiting officers were sitting around our kitchen table. I was a pretty easy sale. My wife was tougher; she was afraid that they would pull the old bait-and-switch on him and he would wind up chipping paint on old hulks. Nonetheless, a few months later, and after an emotional going away dinner, the recruiters showed up late one evening to take Byron downtown to be sworn in.

The next we heard from him was a frantic call from the Great Lakes Naval Training Center: “I’m here. I’m ok. And I have to go.” Click.

It was demanding, but he did well in basic training. The fact that I was only seconds from missing my flight to Chicago to see him graduate from basic still haunts me, but I made it and the ceremony was suitably impressive. We enjoyed a great weekend in Chi Town together.

He continued to excel through the various training schools. The nuclear power training school curriculum is enough to make my head explode-you look at it and decide if you think you can pass. I couldn’t have.

From there, he opted for submarines and helped run the reactor for several years on the USS Nebraska, a ballistic missile sub. I joined the Big Red Sub Club and, in that capacity, was able to go on a one day ride along as the submarine returned from one of its 77 day patrols to its base in Bangor, Washington.

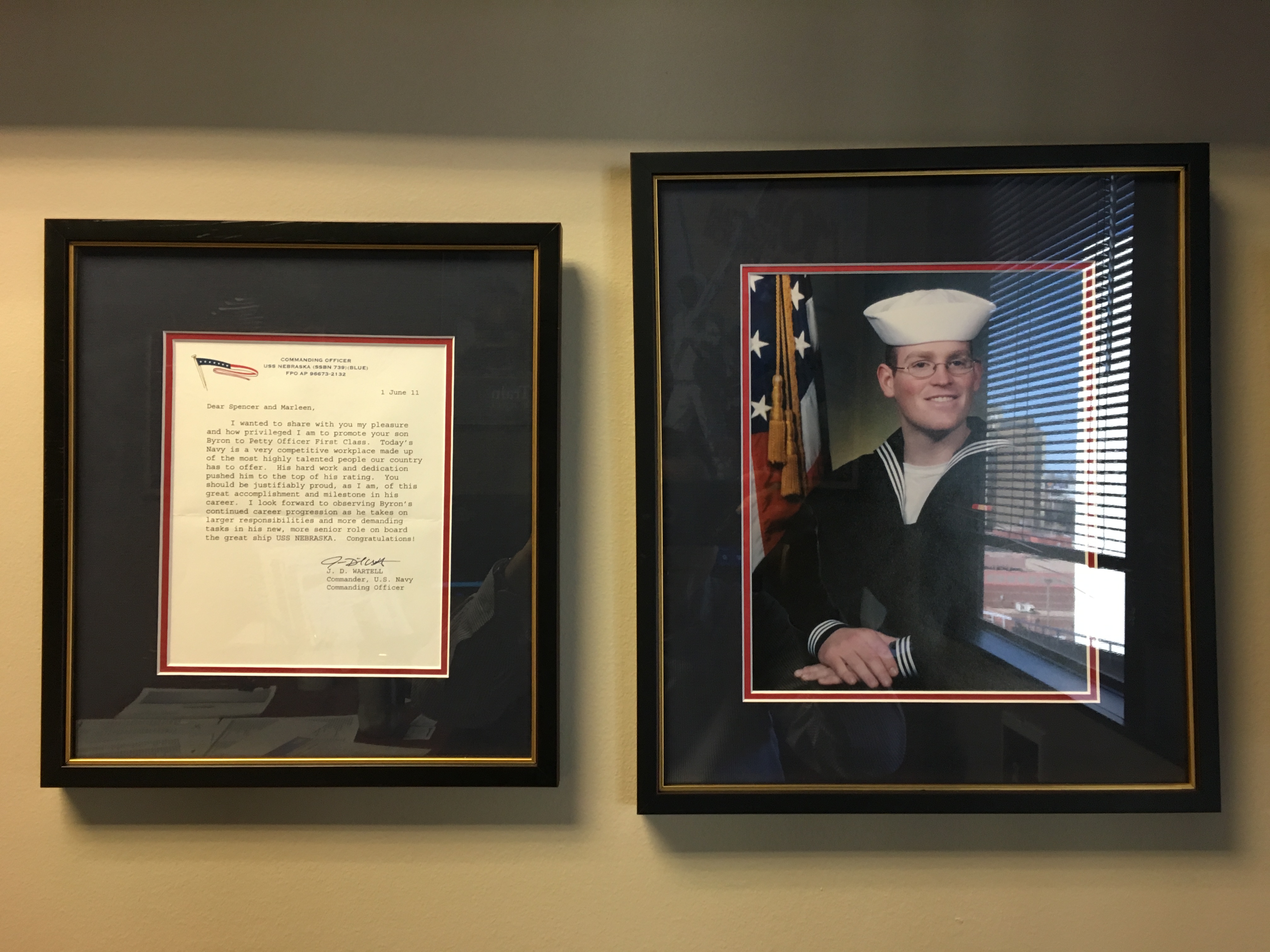

After eight years of outstanding Navy service, Byron finished as a Petty Officer, First Class. The letter his mother and I received from his commanding officer announcing the promotion is impressive and, framed, hangs in my office. He has a shadow box laden with commendations, medals, ribbons and pins.

On the strength of his naval record, and the recommendation of a fellow bubble head, Byron got a job with Google at their data center near Omaha after he mustered out of the Navy. Again, regular promotions. They’ve sent him around the country and from Finland to Ireland on various assignments.

I used to like to tell folks that “The only class that our son passed in college was marching band.” And then go on to tell them how well he had done in the Navy-and now at Google.

However, one time Byron heard me say that and corrected me: “No, dad, I got a D in calculus.”

I stand corrected.