And slightly less unquiet minds

Steve Kinsky’s an old friend. We first met when we were both in a professional organization for health insurance agents. We’ve stayed in touch since we retired. We’re both widely read, although our tastes sometimes differ since Steve has a scientific and mathematical bent that I don’t share; before becoming an agent he was an actuary.

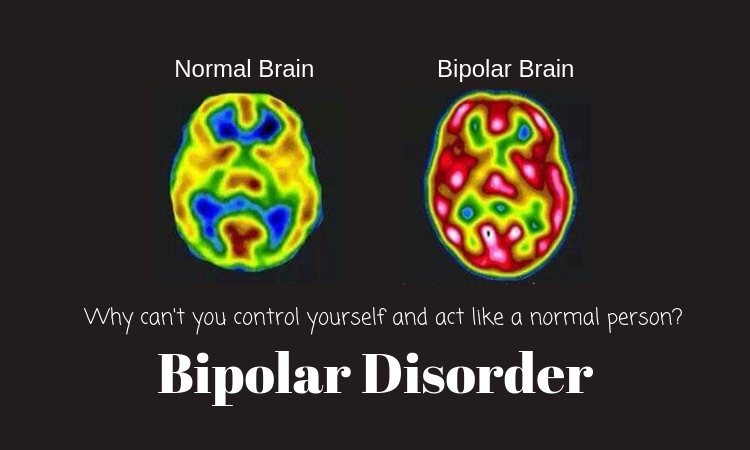

Steve’s known for some time that I have bipolar disorder; I’m not quite sure how he learned about it. He may have read about it in this prior post of mine. But however he came to know, we’ve discussed it more than once.

Last time we met, he suggested that I take a look at a book he’d recently read about bipolar called An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness by Kay Redfield Jamison. Published in 1997, the book is beautifully written and makes compelling reading.

“Racing down the hallway naked”

Like most illnesses, bipolar comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. Or, to state it more precisely, it comes with varying levels of intensity. In my case, it was relatively mild. But that doesn’t mean that I wasn’t involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital as a young adult. Or that I didn’t have wild mood swings between manic, sleepless highs. And lows that left me carefully planning my own destruction. Rather, it means that I never, as my psychiatrist once told me of other cases he knew of, “ran naked down the hallway of a psychiatric hospital screaming at the top of my voice.”

Judging from Jamison’s book, my guess is that her disorder is of the more severe variety. While she’s a brilliant author and clinical psychologist who specializes in this illness, she’s gone beyond the planning stage and actually attempted suicide. She’s also gone on the wild spending sprees that are typical of the disorder. I, on the other hand, only suggested to my business partner the completely inappropriate purchase of luxury cars to “prove” how successful we were. He immediately, and fortunately, scotched the idea.

In short, while I’ve had more than enough “near misses” to make the lives of my family and myself plenty miserable at times, Jamison was on an emotional roller coaster that continued unremittingly for years at a time.

The agony and the ecstasy

Jamison describes her experience with bipolar as a love/hate relationship. That’s fitting. As is typical for this condition, I resisted taking medication for literally decades after I was first diagnosed. Pride. Denial. And, in my case, a belief that my conversion to Christianity would make medication unnecessary. All played a part. As they did to one degree or another in Jamison’s life.

But at least as important was that bipolar’s the sort of illness that one can become attached to. Jamison writes about it. I’ve felt it. The seemingly inexhaustible energy. The perceived brilliance of mind. Even now, years after the condition has been well controlled by medication, I occasionally feel a wistful fondness for those exhilarating times of mental acuity. Until, that is, I recall the inevitable and crushing lows that follow the euphoria.

It’s estimated that 2.3 million Americans, or nearly 1% of the population, are bipolar. Suicide is the number one cause of premature death among people with the disorder, with 15 to 17% taking their own lives. Those aren’t good odds. If you suspect that a loved one, or you, are wrestling with an unquiet mind, figure out a way to get help.

You can start by clicking here.